What happened to xBERT and T5?

We don’t see any scaled-up BERTs anymore. The majority of LLMs (Claude, GPT, Llama..) are decoders. BERTs deprecated in favour of more flexible forms of T5, which are mostly complementary to decoders.

Encoder–Decoder models were the default choice in the original Transformers paper, which is a machine translation paper. But the broader question of model selection remains an open research problem, partly because scaling LLMs so aggressively tends to make architectural choices feel like secondary optimizations. (If you can afford to be optimistic, why stay deterministic?) In practice, researchers often set aside the Encoder vs. E–D vs. Decoder debate and instead build ever larger, seemingly “dumber” models that can, in fact, memorize and generalize better. They are Charlie Babbitt’s American Dream of the Rain Man.

That being said, there have been embarrassing attempts to make encoder and encoder-decoder models work at the level of decoder-only models in terms of performance and scale. The researchers typically ran into 3 caveats:

Training objectives and Data Efficiency

A fundamental difference is the pre-training objective. The primary goal of pretraining is to build a useful internal representation (structure of language & the human interpretation of the world encoded in the training data) that can be aligned for downstream tasks in the most efficient and effective way possible. The better the internal representations, the easier it is to use these learned representations for anything useful later. GPT-style models are based on next token prediction, which generates new training targets for every position in the text. Each time the model predicts a new word, this generates a new set of possible sequences based on the predicted word. In contrast, BERTs only predict a small fraction of tokens.

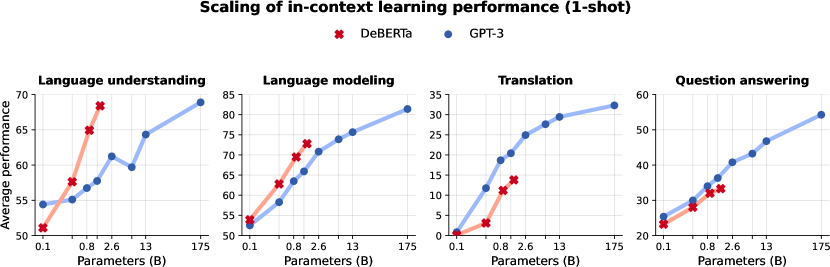

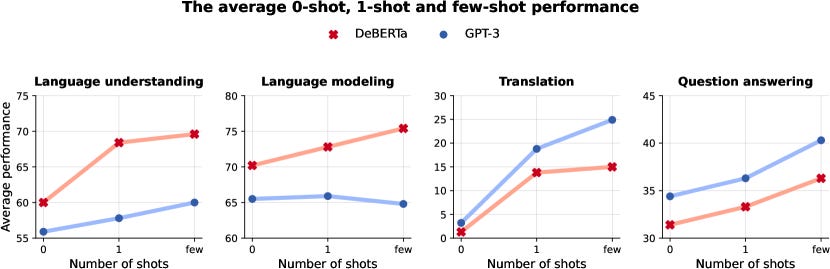

This inefficiency has concrete implications. For example, the DeBERTa-1.5B model (an encoder model) was trained on 3× more data and 3× more FLOPs than GPT-3-1.3B yet only matched its in-context learning performance.1 Only a small amount of tokens are being masked while regular language models use close to 100% of tokens. In other words, to reach parity, masked models required far more compute. This compute/param tradeoff and heavy cost makes pure BERT/T5 scaling unattractive and

somewhat deprecated.2

Data efficiency is not a model selection problem per se but a general machine learning problem, so I decided to keep it under the same section. It is expensive to understand the impact of domain-specific datasets on model capabilities, as training at large FLOP budgets is required to reveal significant changes on tough or emergent benchmarks. Given the increasing cost of experimenting with pre-training data, how does one determine the optimal balance between the diversity in general web scrapes (CC) and the information density of domain-specific data? – Some researchers have studied the efficacy of domain upsampling as a data intervention during pre-training to improve model performance.

There are a lot of tangents to explore for finding better pre-training data pipelines, but it often collapses to a simple question: how much compute are you willing to burn finding better pre-training pipelines when all the compute can be poured into YOLO runs of “high quality” training runs that appear to solve the pre-training objective outright? Since many important model capabilities emerge with scale, trying to explore this design space at small compute budgets is often ineffective: observations made about the effects of the pretraining data mix typically do not transfer to larger models or training budgets.

Architectural complexity

Encoder-only (BERT) and encoder-decoder (T5) models also face architectural overhead. In an encoder-decoder model, the encoder runs once and produces an output memory which is stored and kept fixed. During the decoding step, each new output token generated requires querying that encoder memory state to pull in relevant information. This repeated use of encoder outputs is what makes inference expensive in T5-like models. By contrast, decoder-only models can cache past key/value states so each new token only attends to itself and prior context. No need to keep attending to a separate encoder memory every step. This makes generation much faster as sequence length grows. For anecdotal reference, in multi-turn chat or long-context settings, an encoder–decoder model must re-encode all prior user history at each turn, whereas decoder-only models simply append new tokens and reuse cached context. In practice, this caching efficiency is crucial for large open-ended dialogue and reasoning tasks.

Inference Efficiency

Language models when fine-tuned on downstream tasks may lose previously learnt information during pre-training (catastrophic forgetting). Encoder–decoder models also introduce a potential information bottleneck between encoder and decoder. As layers deepen, the encoder’s final representation may lose fine-grained information needed by the decoder, unless careful cross-layer connections are added. Hyung Won Chung recently gave a talk at Stanford CS25 where he said, “In my experience this bottleneck didn’t really make any difference because my experience is limited to 25 layers of encoder of T5. But what if we have 10x or 1000x more layers? I’m not really comfortable with that. I think this is an unnecessary design that maybe we need to revisit.”

Finally, encoder-only models usually need a separate classification “head” for each task (eg. Question Answering, Sentiment analysis). That means if you want one model to handle many tasks, you have to attach and train lots of different heads. During the LLM era, practitioners shifted toward single massive multitask models (e.g. ChatGPT, LLaMA, Claude). BERT-style models became “cumbersome”3 precisely because researchers wanted one model to handle all tasks at once. Decoder-based models can be prompted for any task, avoiding separate heads.

Attempts to scale encoders and encoders-decoders

Researchers did try scaling BERT/T5. For example, Google’s T5 family grew to T5-11B (≈11 billion parameters) in 2020, and multilingual mT5 reached ~13B.4 The latest “Flan-T5 XXL” (11B) showed decent few-shot accuracy (MMLU ~55) after instruction tuning. Microsoft’s DeBERTa reached 1.5B, and its author showed it could match GPT-3 (1.3B) on many tasks using in-context methods (see note 1). But in each case, these models remain far smaller or more expensive than the largest decoder models. T5-11B is an order of magnitude smaller than GPT-3 175B5. DeBERTa-1.5B had to use three times the compute of GPT-3 to compete (see note 1).

Aside from scale, the performance gaps also steered trends. Pure encoder models cannot generate text out of the box and need special workarounds (e.g., diffusion sampling or prefix masking). T5-style enc-dec models can generate but require pairing input-output at inference, which is less natural for open-ended tasks. Consequently, big projects (like OpenAI’s GPT-4, Google’s PaLM, Meta’s Llama) have all used decoder or decoder-predominant designs. Some hybrid approaches emerged (e.g., UL2, GLM, CM3, Mixtral’s …), mixing bidirectional and causal pretraining, but even these use primarily decoder architectures with auxiliary objectives.

Encouragingly, some work shows encoder-based models still excel in niche domains or classification tasks. For example, a 2025 study found that for many hard text-classification benchmarks, fine-tuned BERT-like models still outperform expensive LLM inference.6 But these are relatively narrow tasks.

I think that we can’t have A generalist model but many generalist and many specialist models in the future. This doesn’t need a genius to figure out why. The world is very heavy-tailed, and there are a lot of fundamental trade-offs. We are often compelled to choose one or the other. There will always be some people who know how to use these models like a specialist better than the others. They know how to squeeze out every bit of that last mile value. But, like other skills, anyone can learn how to access these models at their disposal. That being said, frontier AI labs are currently bullish on training better generalist models, and users largely prize broad-generation capabilities and few-shot generality, which favour decoder models.

Yi Tay et al. (page 26, para 3)

Yi Tay et al. (page 6, para 2)